Posteriors and Predictions

In the previous section, we ended up with the following model:

import com.stripe.rainier.core._

import com.stripe.rainier.notebook._

import com.stripe.rainier.compute._

import com.stripe.rainier.sampler._

implicit val rng = RNG.default

val eggs = List[(Int, Long)]((0,31), (2,47), (0,35), (2,40), (0,33), (2,44), (0,30), (2,46), (0,33), (0,30), (2,36), (2,54), (1,45), (1,39), (2,62), (2,54), (1,30), (2,40), (2,48), (1,33), (0,40), (2,38), (0,31), (2,46), (1,41), (1,42), (0,39), (1,29), (0,28), (1,36), (2,46), (2,33), (2,41), (2,48), (1,32), (0,24), (1,34), (2,48), (1,52), (1,37), (0,28), (0,37), (2,51), (2,44), (1,40), (0,41), (0,36), (1,44), (0,32), (0,31), (0,31), (0,32), (0,33), (1,27), (0,40), (2,45), (2,40), (1,46), (0,35), (2,46), (0,34), (1,41), (0,38), (0,34), (2,46), (1,44), (2,49), (2,39), (1,41), (2,37), (1,29), (0,29), (2,41), (2,46), (1,42), (1,34), (1,32), (1,35), (0,32), (1,40), (1,37), (1,38), (1,42), (1,38), (1,36), (0,38), (0,41), (1,51), (1,40))

val lambda = Gamma(0.5, 100).latent

val logFeeds = Normal(lambda.log, 0.1).latentVec(3)

val feeds = logFeeds.map(_.exp)

val eggFeeds = eggs.map(_._1)

val eggCounts = eggs.map(_._2)

val feedsVec = Vec.from(eggFeeds)

val poissonVec = feedsVec.map{i: Real => Poisson(feeds(i))}

val vecModel = Model.observe(eggCounts, poissonVec)

Now, it's decision time. Which feed should the farmer go with?

Finding a Trace (recap)

As we did once before, we'd like to sample this model to get a Trace we can make predictions from, and then check the diagnostics on the trace.

val sampler = EHMC(5000, 5000)

val eggTrace = vecModel.sample(sampler)

/*

sampler: SamplerConfig = com.stripe.rainier.sampler.EHMC$$anon$1@2cb5ec5

eggTrace: Trace = Trace[4][5000][4]

*/

eggTrace.diagnostics

/*

res0: List[Trace.Diagnostics] = List(

Diagnostics(1.0000924117018197, 7021.582570915608),

Diagnostics(1.0000056354238847, 7518.699684366095),

Diagnostics(1.0003606218897734, 6460.616954805255),

Diagnostics(1.0000643336309119, 7671.848255797101)

...

*/

As before, these don't look too bad. Seems like we've got a solid posterior sample that we can make use of.

Making Predictions

We mentioned before that Rainier prefers not to focus on the raw parameter values, but instead to inspect distributions of random variables. That's not quite the whole story: calling predict with a random variable helps us capture our uncertainty about what the parameter values are (sometimes called "epistemic uncertainty", uncertainty from a lack of knowledge), but it does not capture our uncertainty about the inherent randomness of the world (sometimes called "aleatoric uncertainty", or just "noise"). More concretely: even if we knew very precisely to 10 decimal places what the "true" egg-laying rate was for our flock of chickens, we still wouldn't know exactly how many eggs, as an integer, we will get tomorrow.

This kind of uncertainty is modeled in Rainier by the Generator[T] type. Generators are only used once we already have a Model, to make posterior predictions from a sampled Trace.

One way to construct a Generator[T] is from a Distribution[T]. For example, we can predict daily values from a single type of feed like this:

val gen0 = Generator(Poisson(feeds(0)))

eggTrace.predict(gen0).take(5)

/*

gen0: Generator[Long] = Generator()

res1: List[Long] = List(44L, 42L, 24L, 29L, 37L)

*/

It might be more interesting to compare two different feeds. For example, here we are sampling the difference between feed 0 and feed 2:

val pairGen = Generator((Poisson(feeds(0)), Poisson(feeds(2))))

val diffGen = pairGen.map{

case (n0, n2) => n2 - n0

}

eggTrace.predict(diffGen).take(10)

/*

pairGen: Generator[(Long, Long)] = Generator()

diffGen: Generator[Long] = Generator()

res2: List[Long] = List(13L, 6L, 9L, 2L, 4L, 10L, 4L, 25L, 17L, -2L)

*/

There are a couple of things to notice here: first, we're using Generator() to wrap a tuple of two Distribution[Long] objects to produce a Generator[(Long,Long)]. Generator() will try to adapt simple compositions of distributions (tuples, sequences, maps) into their corresponding generators. It will do the same for simple compositions of Real values (which become Generator[Double]).

Second, having produced pairGen, we can use map to do further transformation (in this case, finding the difference between the two longs produced by the distributions). We could also use flatMap and zip to combine generators. Generators are very flexible, more flexible than Real, but the trade-off is that they can only be used in this predictive phase rather than for inference.

Anyway, let's plot these results:

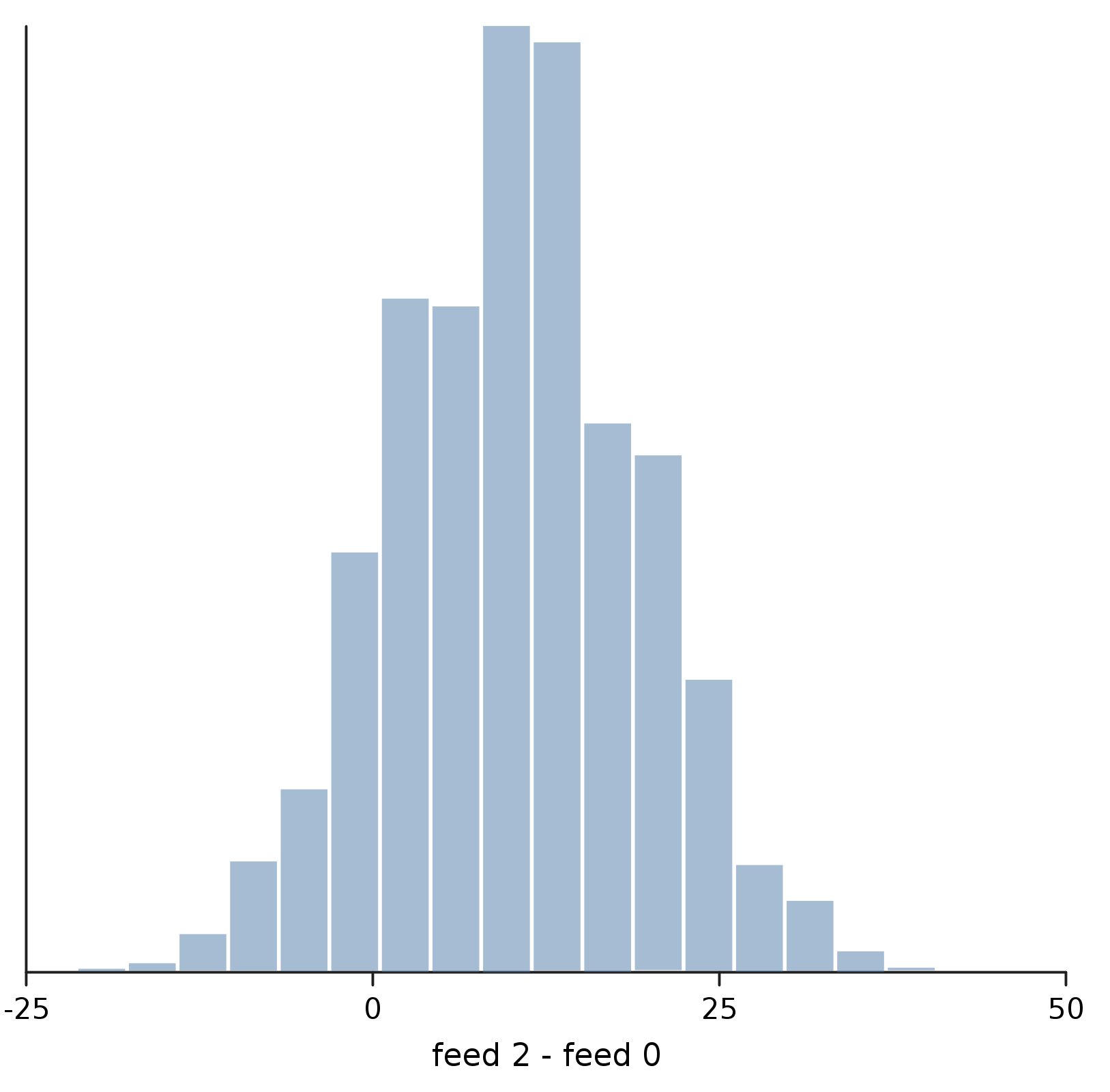

show("feed 2 - feed 0", density(eggTrace.predict(diffGen)))

Even though we can see that feed 2 is clearly better than feed 0, there's enough combined epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty here that there can still be days where a chicken on feed 0 would lay more eggs than one on feed 2.

Even though we can see that feed 2 is clearly better than feed 0, there's enough combined epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty here that there can still be days where a chicken on feed 0 would lay more eggs than one on feed 2.

Making Decisions

At the end of the day, the most valuable thing your model can usually do is to inform an actual decision. Staring at plots and trusting your gut is certainly one way to do that, but there's a better way that doesn't seem to get enough attention, which goes like this:

- Choose a utility function

f(d,g)that tells you how good decisiondwould be, if predictiongturned out to be true - For each possible decision

d, find the expectation off(d,g)over all posterior predictionsg - Pick the decision with the highest expectated utility

In this case, let's imagine that the 3 feeds cost $2.80, $3.30, and $4.00 per day, respectively, and that the eggs sell for $0.12 each. We can construct a utility function that just tries to compute the profit for a day's worth of eggs:

val feedCost = List(2.8, 3.3, 4)

val eggValue = 0.12

def profit(eggCount: Long, feed: Int): Double =

(eggCount * eggValue) - feedCost(feed)

Then we can construct a generator that produces the daily profit for each decision:

val profitGen = Generator(feeds.map{rate => Poisson(rate)}).map{counts =>

counts.zipWithIndex.map{case (n, i) => profit(n, i)}

}

/*

profitGen: Generator[Seq[Double]] = Generator()

*/

Finally, we can sample from and then average over the posterior for that generator.

def average(predictions: Seq[Seq[Double]]): Seq[Double] =

predictions.reduce{(left, right) =>

left.zip(right).map{case (l,r) => l + r}

}.map{v => v / predictions.size}

average(eggTrace.predict(profitGen))

/*

res4: Seq[Double] = List(1.2804619999999929, 1.3001459999999938, 1.3193119999999903)

*/

According to this, the more expensive feeds are worth it: the extra eggs you get do, on average, cover the extra cost.

However, that's a very simple utility function. (In fact, so simple that we could have just computed it with averages instead of by summing over the posterior.) What if we wanted something more sophisticated?

For example, imagine that cashflow on the farm is very tight, and that if there's ever a day where the egg sales don't cover the feed, that can cause problems. You might decide to penalize that ever happening with a "cost" equivalent to $20:

def utility(eggCount: Long, feed: Int): Double = {

val net = profit(eggCount, feed)

if(net < 0)

net - 20

else

net

}

val utilityGen = Generator(feeds.map{rate => Poisson(rate)}).map{counts =>

counts.zipWithIndex.map{case (n, i) => utility(n, i)}

}

average(eggTrace.predict(utilityGen))

/*

utilityGen: Generator[Seq[Double]] = Generator()

res5: Seq[Double] = List(0.6185540000000184, 0.5232100000000048, 0.3516360000000067)

*/

Modeled this way, the choice flips: it's better to take the lower-risk option of the cheap feeds than to try to squeeze out every last cent of profit but put cashflow at risk.

Of course, now you're down to a different gut decision: which utility function do you go with? But at least making that meta-decision once will help you easily make many concrete decisions down the line.

Fin

Thank you for making it all the way through this overview. We hope you enjoy trying out Rainier!